The outrigger canoe has been central to the development of Hawaiian culture. So important was the canoe that the building of a new canoe was a significant event involving most of the members of a village: priests, craftsmen, laborers, helpers. From choosing the right tree to launching the new canoe, each step in the process had to be done correctly with the proper ritual and respect to preserve the life of the tree in the canoe and create a canoe that would, in turn, sustain the lives of those who used it.

In Hawaiian tradition each canoe is a living entity, with its own spiritual power or mana. We entrust our lives to our canoes and we treat them with respect.

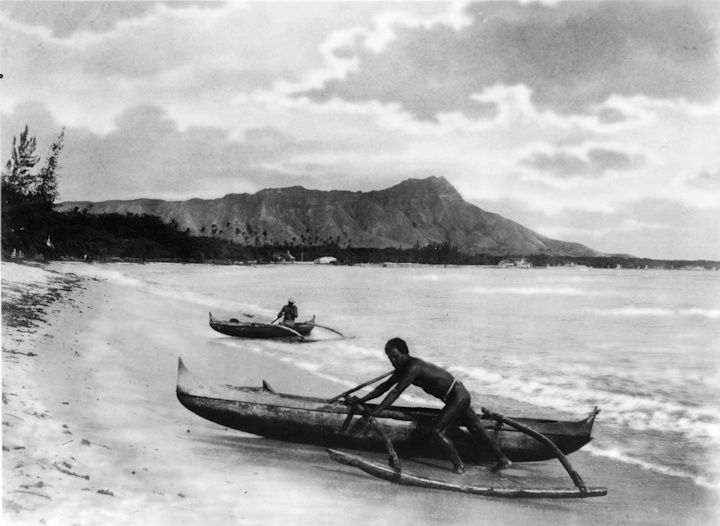

The open-ocean conditions surrounding our islands led to the development of an outrigger canoe different from those of other Pacific islanders. The Hawaiian outrigger is relatively unadorned, with fore and aft hull covers (kupe) and a splashguard (pale kai) to cope with ocean waves and chop.

Although outriggers now are raced throughout Polynesia, outrigger canoe racing, ancient and modern, seems to have originated in Hawai‘i. There are records of ancient Hawaiians racing for fun and for wagers, sometimes including life.

Today’s HCRA-approved racing canoes are standardized in length and weight to allow both an observance of tradition and a level playing field. To race in HCRA-sanctioned events, including events sanctioned by our association, Na ‘Ohana O Na Hui Wa‘a, canoes must weigh a minimum of 400 pounds without ‘iako, ama, or seat covers, and can be no longer than 45 feet. While most associations in the Islands, including ours, allow clubs to race fiberglass canoes, at the annual Hawai‘i state championship regatta all crews must race in koa canoes.

The diagram shows the Hawaiian names of most parts of the canoe. We use both Hawaiian and English terms, but you should be familiar with the Hawaiian nomenclature.

‘Olelo O Ka Wa‘a

Hawaiian Language: paddling terms by Terry Wallace

Ho‘owala‘au wa‘a - canoe talk.

Ha‘awina (lesson)

In every sport or job there is a special language. Words are used in this specialty like no other. For example, Navy terms. This also works for paddling the Hawaiian canoe.

If Na Ho‘okele (steerers) use the same language for commands universally, there will be little or no confusion on the part of the paddlers. These commands can and should be used to familiarize the crew with the language. The same language used consistently also gives Ho‘okele (steerer) control of the canoe and used to the idea of giving commands.

UNE = pronounced OO-NAY. To “lever.”

This is the action MUA (stroker and sometimes others) takes to help HO‘OKELE (steerer) turn the bow of the canoe going around the turn flag. This can be ANY movement of the paddle, from a J-stroke to paddling toward the hull. I have heard this term mis-pronounced UNI = OO-NEE. This word is not in the Hawaiian dictionary.

KAHI = pronounced, KAH-HEE. To “cut.”

Holds the paddle still, blade “cutting” in the same line as the canoe. No “action” taken.

PAHI = pronounced PAH-HEE. Edge, the blade or knife edge.

These are commands that can be used by Ho`okele in the canoe.

‘E ‘E! = pronounced ay ay (this is hard to describe..... actually a very short “‘e”). Get in the canoe!

HO‘OMAKAUKAU! = pronounced Hoh oh MAH cow cow. Get ready or get set!

This can be whatever you think “get set” means. Paddle across the gunwales, or poised to plant the blade in the water or whatever.

KAU! = pronounced kah oo. Place (or plant) the blade!

If it’s training:

HOE = pronounced ho aee. Paddle! And off you go.

If it’s racing:

HUKI!!!!!!!!!! = pronounced hoo key. Pull, GET INTO IT!

All of the following terms are from either Hawaiian Dictionary by Pukui & Elbert or The Hawaiian Canoe by Tommy Holmes

Many of these terms have other meaning as well as allegorical meanings or Kaona (the hidden meaning) other than used here.

Some kinds of Hawaiian Canoes:

- wa‘a: generic term for canoe

- heihei: a race of any kind including a canoe race

- ‘au wa‘a: a fleet of canoes

- ‘auwa‘a ‘a ho‘`apipi: two canoes hastily joined to form or to use as a double canoe

- wa‘a kaulua: another term for double canoe

- kaukahi: a single canoe with an outrigger

- kialoa: a long, light, and swift canoe used for racing & display. This term may also refer to a beautiful woman and her shape. Queen Ka‘ahumanu was referred to as “Kialoa” in her youth.

- Ko‘okahi: OC1

- Ko‘olua: OC2

- Ko‘oha: OC4

- Ko‘eono: OC6

- Wa‘a ‘Apulu: an old, worn-out canoe. Also an old person. You see, the old time Hawaiians DID have a real sense of humor.

Hawaiian Language: some rules by Terry Wallace

‘Olelo o ka wa‘a - canoe language.

Lula kulu. (Some rules)

When we get through these, we’ll go on. This is probably the hardest part of the whole program. Hopefully, you’ll get “kinda’ close” to the pronunciation. Don’t depend on your friend who “went to Hanalula once twenty years ago so he probably knows.” Uh, uh, oh no!

Pronunciation:

There are 12 letter symbols or “sounds” in the Hawaiian language. Vowels — a-e-i-o-u — are ALWAYS pronounced the same. Spanish/Italian is the closest to Hawaiian vowel sounds.

As in;

- a = ah

- e = aee

- i = ee

- o = oh

- u = oooo

EXCEPT!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Actually, there are more than 5 vowel “sounds.” More like 20!

Vowels can have four different sounds, regular, short, long (or with emphasis) and short with emphasis. As in ‘ōlelo, emphasis is placed on the first vowel and none on the others. ‘Okina (hamza) is a glottal stop similar to the oh’s in English oh-oh. This symbol is a small forward slash like an apostrophe, only backwards (‘). It should look like a “6,” only much smaller. I’ve seen “ ’ ” (like a tiny 9) which is NOT correct.

Note: some older browsers don’t recognize the ASCII code for the kahako (macron), which is an emphasis line placed over a vowel. If your browser doesn’t recognize the ASCII code, you’ll see the code instead of the symbol.

So the vowel sounds are: a, ‘a, ā, ‘ā + e, ‘e, ē, ‘ē + i, ‘i, ī, ‘ī + o, ‘o, ō, ‘ō + u, ‘u, ū, ‘ū.

Later we’ll do “rising diphthongs.” (no, your bikini isn’t too tight!)

Huikau ‘e? (Confused already?) Don’t sweat the small stuff. It’s all small stuff and will become obvious later on. Mahope! (After!)

Consonants are; h, k, l, m, n, p and w. These are pronounced just like English, EXCEPT for the “W” which can change, depending. “Depending on what?” It can be like “W” or “V” or “VW,” depending. Depending on where in the regional accent or especially where in the word it’s located. So, if you say, “HaWai‘i” or “HaVai‘i” or “HaVWai‘i,” any of these is OK.

Another thing - “All them dang Haiwyun words start with ‘K.’” Right! That’s because “the” in Hawaiian can be “ka” or “ke.” Oh-oh, here comes another one! OR - “nā.” (notice I emphasized nA). Nā is the “S” in this language. Nā precedes any word you want to make two or more of. “The man” = ke kanaka. “The men” = nā kanaka. ‘īako is ‘īako is ‘īako. Notice it’s ‘īako, not ‘iako (look closely at the “i”). Emphasis here is on the first vowel in the word. One, two or twelve of them: ‘īako.

(I suppose it’s always plural because that’s the way they’re used. Two or more at a time. What good would one do?)

OR you can say, kānaka which is the same as nā kanaka. Emphasis is on the capitalized vowel.

Since “Hawaiian” is an Anglicized word, in future we will use the term “Maoli” instead. This is a common Polynesian word meaning roughly, “original people” (or a variation of that), as opposed to immigrants.

As in;

- Hawai‘i = Maoli

- Tahiti/Marquesas region = Maohi

- Aotearao (New Zealand) = Maori

Ho‘opau ka ha‘awina (end of lesson)

Kū‘auhau mai (that’s me, my name & I’m here, mai, not dead or somewhere else)

Culture & Tradition: Ancient History by Terry Wallace

I have read and heard many say, “Why must we do this,” or “why is such-and-so done this way?”

One of the answers is “Culture and Tradition.” However, if you need expert advise on technique or construction, you are better off with the likes of Walter, Tay, the Foti’s and many others. I paddle and teach the way I do because real coaches the likes of them taught me years and years ago. Recent progress adjusts our techniques, but the basics are still muscle the canoe forward by paddling.

The author is a Hawaiian History instructor & M.A. candidate in Military History, thesis on Hawaiian Military history, 1790-1810.

Culture: the acquired ability of a people to recognize and appreciate generally accepted esthetic and intellectual excellence.

Tradition: the handing down of opinions, doctrines, practices, rites and customs from age to age by oral communication.

The Hawaiian Outrigger Canoe was developed by the indiginous people of pae ‘aina (Hawaiian Islands) for two thousand years. Outrigger canoes and their counterpart, double-hull, have developed over time mainly for open ocean conditions in the Hawaiian Islands. Canoes were used in many ways, just as we use automobiles today. From racing cars to heavy trucks for moving goods to busses for transporting people. In Hawai‘i, the ocean was the highway for those who could afford it. Outrigger canoes used for fishing were relatively small with a small crew of two or three. These banana-shaped canoes had a large bottom to hold the catch. This small size and curved shape is also useful for surfing as they are very maneuverable and the shape lessens the chance of pearl-diving.

Racing probably started when fishermen challenged each other to be the first in to offer prize fish to their chief. A racing canoe and crew was expensive. The racing canoe was called hei hei wa`a and was similiar to today's racing canoes. This was also a term of endearment to a beautiful woman; long and sleek with a widening rear end. One nickname for Ka‘ahumanu was “Hei hei.” She was considered the most beautiful woman anywhere (at age 18) by Vancouver when visiting Kamehameha. Often, noho (canoe seats) were named for a particular paddler who occupied that seat rather than #1, #2 etc. One of the favorite paddlers of Kamehameha was a Ho‘okele (steerer) by the name of Kainaliu. His name lives on at an ahupua‘a (land division) and community by the same name in Kona, Hawai‘i Island. Kainaliu literally means “bail the bilge,” Ka being the bailer, so we know he was at least in the canoe. By the way, Kona means leeward and there is a Kona district on every major Hawaiian Island except Maui. Waikiki and its adjacent areas is the old Kona side of O‘ahu.

Chiefs raced against each other, often betting on the outcome. This betting practice eventually led to banning of racing by Ka‘ahumanu under influence of the missionaries.

Long before the missionaries arrived, Kamehameha lost interest in canoes when he foresaw the coming of Western Trade. He also found Western sailsets more efficient with the ability to sail closer to the wind using fore-and-aft sails with gaff rigs and ketch sail shapes. Western vessels could carry more goods with a similiar sized crew of a double hull. Kamehameha became, after uniting the islands by warfare, primarily a trader. The thousand peleliu double-hull and outrigger canoes built for the amphibious invasion of Kaua‘i then sat rotting in O‘ahu sun. Most of these were made of koa trees from Hawai‘i Island, denuding the forests. However, many were carved from other woods, including driftwood spruce from Northwest America.

Today’s racing hulls are also specialized. Regatta racing in Hawai‘i State is strictly in hollowed out koa wood canoes. These are often shaped in the “Tahitian Style” with low gunwales. Shape, length and weight requirements are rigid in Hawai‘i, mainly based on “culture & tradition.”

Open ocean long-distance racing canoes have higher gunwales often with a pronounced tumble-home. Long-distance racing is practiced in a variety of shapes and materials from koa to graphite, ho‘eono (OC-6) to ho‘ekahi (OC-1). At the Moloka‘i to O‘ahu races, one will see this variety of shapes, from fat-assed Malia to long and sleek “racers.”

References: The Hawaiian Canoe by Tommy Holmes, Hawaiian Antiquities by David Malo, History of the Hawaiian People by Abraham Fornander, Ruling Chiefs by S.M. Kamakau and my late teacher Mary Kawena Pukui.

When frustrated: Malie a me waianuhea o ka uka.

Stay calm & cool like a misty mountain breeze.

Na ‘ike mo‘olelo a me ha‘awi na hana hou mai?

More “culture & tradition” another time?

Culture & Tradition: Recent History by Terry Wallace

After the overthrow of the Kapu system by Liholiho (urged on by Ka‘ahumanu and Keopuolani), chaos ensued. It was if the Pope and President declared that religion and government was all rubbish. Ka‘ahumanu declared herself Kahina Nui, effectively Prime Minister, and no one resisted that strong-willed woman. She effectively controlled Liholiho (Kamehameha II) who was only about 21 years old.

Ten months later, the 1st company of Calvinist missionaries arrived in Kailua-Kona. The Thurstons with Dr. Holman and wife were the only members allowed to land and were appalled at the dry conditions. (I imagine the Hawaiians were appalled by the missionaries smell after six months at sea!) The rest of the company was sent on to O‘ahu. Eventually, and after much hard work and resistance, the missionaries got control of the Royalty. Ka‘ahumanu banned canoe racing before 1830 and the sport died out. In fact, anything equated with fun was banned. There was intermittent racing of whale boats, shells and other vessels in the mid-1800’s, but not until Kalakaua was elected king did boat racing become a regular event.

Kalakaua revived shell regatta racing in Honolulu Harbor. Outrigger canoe racing followed, using any kind of canoe available. In Tommy Holmes’s book The Hawaiian Canoe, photos show crews of 5 and 6 paddlers racing against each other.

In 1906, Prince Kuhio had the racing canoe, A or A‘a (pronounced AH or AH‘AH, this word has many meanings from “fiery” to “giving” and probably only Kuhio and Moku‘ohai really knew what it meant). The canoe was built in Kona by Kahuna Kalaiwa‘a Moku‘ohai (Master Canoe Builder Moku‘ohai came from a family of canoe builders whose descendants still live in the Kealakekua Bay area). This hei‘hei wa‘a had a long and successful carreer and is now housed in Bishop Museum.

In my opinion, Prince Kuhio is the father of International Hawaiian Canoe racing as Duke Kahanamoku is the father of Surfing. If Hawaiian Canoe racing is included as a demonstration sport in the next Olympics, Prince Kuhio should get recognition!

War, politics and social conditions caused interest in the sport to wax and wane. The late 1920’s and up until WWII was a good time for racing. Some of the women’s teams were strong with competition including swimming races before and after canoe events. Especially for the Kealakekua and Honaunau teams. These teams were mostly fishermen before outboard motors. All they did was paddle. Then, after fishing all night, they would train! Needless to say, Honaunau won almost every race. If they didn’t win, it was because they hadn’t entered.

After WWII, interest revived when the men came home. During the war, canoe surfing continued along Waikiki, taking the canoes out through the openings in the barbed wire strung along the beach.

When paddling started up again, racing equipment had not changed. Nor had techniques. Canoes were wood, mostly koa hulls with hau wood ‘iako and wiliwili wood ama. Most of these canoes were survivors of the resurging interest of the early 1900’s. Paddles were made from whatever wood was available. Like the old “plank” surfboards with no fin, one time out in the water and your equipment had to dry for a couple of days. Imagine a 3 to 5 pound paddle with a lau (blade) 13 X 21 inches. The shaft was straight with no grip. There were generally two sizes, child and adult.

Paddle shape created paddling technique. Really slow! But with that big blade, paddlers could generate power. Try it sometime, that big paddle will make a believer out of you!

Outrigger Canoe Travel by Terry Wallace

‘Olelo No‘eau - a proverb:

‘Au i ke kai me he manu ala. - Cross the sea as a bird.

When Captain James Cook landed on Kaua‘i and later on Hawai‘i, he gave the island group a name, after his patron James Montague, the Earl of Sandwich. For the next seventy-one years the islands were called (by outsiders) the Sandwich Islands. The connotation rubbed local inhabitants the wrong way.

These eight major islands form four separate counties. Starting at the oldest in the northwest, Kaua‘i and Ni‘ihau is one county. O‘ahu is its own county. Next comes Maui County, which includes Moloka‘i, Lana‘i and Kaho‘olawe. At the southeast corner of the group lies Hawai‘i, with more square miles than the rest of the islands put together. Moku O Hawai‘i (Hawai‘i Island) is the youngest and is still growing by lava flow.

The greatest distance between the islands is between Kaua‘i and O‘ahu at about 82 miles (137KM). Kaua‘i came to be known as a “separate kingdom”. And Kaua‘i was different from the rest of the islands in many ways. All the islands were different kingdoms and warfare, especially in the late 1700’s was rife. However, trade continued to flourish in the only way possible, by sea. Canoes allowed the people of these islands to become accomplished fishermen, merchants, sailors, and amphibious warfare specialists.

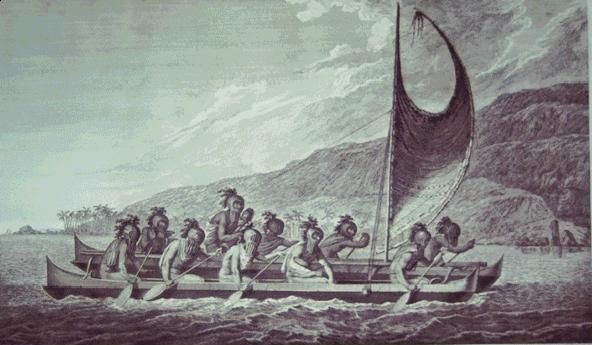

Na Kanaka Maoli (The Original People), both paddled and sailed and most canoes were specialized in their use. The largest were double canoes, wa‘a kaulua. Trade goods consisted of specialties traded to those who had another kind of specialty, such as ko‘i (adze blades) from Hawai‘i for a special dried fish only available from Moloka‘i. These travelers also devised special, non-perishable foods such as popo poi, (balls, different from Aotearoa - New Zealand) to keep them in their journeys.

Then, in 1795 and after provocation from both sides, the King of O‘ahu, Kalanikupule, plotted to assassinate Kamehameha, the King of Hawai‘i. This attempt was thwarted by foreigners and Kamehameha subsequently invaded and conquered O‘ahu by way of Maui and Moloka‘i.

In the series of canoe amphibious invasions, some 1,200 double and outriggers carried more than 12,000 warrior-paddlers (about the same as the Norman invasion of England in 1066). They crossed Ka‘iwi Channel between Moloka‘i and O‘ahu, landing on an early morning high tide in mid-August. At that time, the Waikīkī district extended for ten miles (17KM) from what is now downtown Honolulu almost to the foot of Koko Head. Most of the army landed in Kahala, then moved toward Nu‘uanu between the fishponds and the mountains. After six days, Kamehameha pushed the remnants of the O‘ahu army off the Pali and took the island.

It wasn’t until several failed invasion attempts and much negotiation that in 1810 Kaua‘i also came under the rule of Kamehameha. Thus, the Kingdom of Hawai‘i and the term “Hawaiians” was born, under the rule of the richest, most populated and predominant island, Hawai‘i.

In 1849, the term, “Sandwich Islands” was officially discarded by the Legislature and the term “Hawai‘i” began.

Ka pau ‘ana ihola no ia o ka‘u mo‘olelo - So ends this story.

Sources; Kamakau, Fornander, Papa I‘i, Pukui, Joesting, Kane & Wallace.

Outrigger Canoe: Momoa by Terry Wallace

Momoa or moamoa has no function. Or does it?

Na Maoli, (same as Maori and Maohi) the original people of what is now called the State of Hawai‘i, were not known for decorating functional tools. Unlike others, Maori for example, wa‘a were not usually intricately carved or decorated. Everything was functional. Parts were tied together by different systems, some being quite elaborate, but function was the main element. To quote Tommy Holmes in The Hawaiian Canoe:

any nonessential ornamental design feature either structurally weakened a canoe or resulted in a canoe that was less rugged and break-proof than a simpler and cleaner craft. To survive the pummeling surf and raging channels of Hawai‘i, every design feature, every component, every inch of the Hawaiian canoe had to be functional and rugged.

So it was with Momoa. Looking at the extreme aft end, ka hope (kah hopay), you should find a small flat spot. As if the manufacturer had not quite affixed the top (kupe hope - koopay) to the hull (ka‘ele) correctly, leaving a small projection about 1” to 1.5” or so of the top of the hull visible. What could this be for? Fastening spray covers? Tying the ama to the manu (mahnoo) in heavy seas to prevent excess movement? ‘Aole - no! It's where your canoe akua rides to protect you while you are at sea.

Remember, Moana (the ocean), doesn't care at all about you. And you’re too busy to be concerned with yourself. So hopefully, Akua, your team’s or canoe’s personal spirit will protect you. This thought may also make your crew more aware of surroundings, rigging, etc. (I choose the term “spirit” to avoid religious controversy. Don’t even bother to respond: I’ll delete at first hint.)

How this custom got started:

About 700 years ago, the religious Kahuna, Pa‘ao, went to Kahiki to find new blood for a king. To make a long story short, he finally selected Pili Ka‘aiea and asked him to come to Hawai‘i. As they sailed from Raiatea Island, heading back to Hawai‘i (island), the Tahunga (priest) Makuakaumana called out from the top of a cliff that he “had been left behind.” Pili replied that “the canoe is filled, but if you leap from the cliff, you can ride there (on the Momoa).”

Makuakaumana then leapt from the cliff and flew toward the canoe, meanwhile changing from a man into a spirit so that he could ride on that small place. From then on, momoa was considered an essential part of any canoe, outrigger or double.

Since the advent of fiberglass canoes and the story of momoa being “misplaced,” many manufacturers and carvers have either moved, redesigned or forgotten ka momoa. Some of us believe that momoa is an essential and important design feature of the Hawaiian canoe. If you believe in Custom, Culture and Tradition and that your canoe needs its own “feeling,” spirit or “akua”, or whatever you choose to call it, then include momoa.

Bibliography: OHA - Jan. 1988, Stokes - HHS paper #15, Abraham Fornander - “The Polynesian Race.”

Malama pono (Take care)

Outrigger Canoe: Manu by Terry Wallace

Ka‘upu hehi ‘ale o ka moana. The ka‘upu bird that steps on the ocean billows. An allegory or symbolic representation to a sea-going vessel.

-Pukui

Manu. This term in much of Polynesia means “bird.” The two projections on either end of an outrigger canoe (ka wa`a or te waka) are called manu (mahnoo) or birds. These projections are functional as well as traditional and in some cases religious. In some parts of the Pacific, the manu is minimal and in others, they stick up several feet. Most sea-going vessels through the ages have had some kind of up-swept bow and stern. Viking ships employed end-pieces with god-manifestations on either end. All sea-going vessels in Polynesia and throughout the rest of the Pacific employed up-swept end pieces. Some are fancier than the rest. Lagoon and river canoes seldom used this device. They were simply not functional in that environment.

The functional purpose of the manu mua (moo-uh) or ihu (eehu), - both meaning forward, was as a “cutwater” when plowing through waves. If a wave does come over, its power is minimized and is further cut by the pale kai - splashguard (pahlay kaee). The purpose of the manu hope -rear (hopay) was to prevent, or at least minimize a following sea from “pooping the vessel,” that is, coming over the stern.

Why the term “manu” is used is a little harder to explain. The sea can be a scary place. Moana, the great ocean simply does not care one whit about the people that ride on her skin. But why a bird for your canoe, and not one of the mammals or fish? Simply put, one wants one’s canoe to ride on the sea, not in it. Polynesians held much significance in birds. Birds were often considered a manifestation of the human spirit leaving earth and going to heaven. The name ‘Iolani, one of the many names of Liholiho or Kamehameha II means the “Hawk of Heaven” or “Royal Hawk,” used because of its high flight in the heavens.

Birds were also observed to “flow” on wind currents at sea, having the ability to ride over waves without touching the water. If one observes a canoe and uses a little imagination, a bird is visible. Manu ihu being the beak, mo‘o (moh oh) or gunwales the wings held back in a gliding position and manu hope, the tail feathers. By employing bird symbols, both visible and in the mind, it was hoped that a sea-going canoe would symbolically “ride” the air currents over dangerous seas.

Pipi holo ka‘ao, the end.

Ku‘auhau mai.

References: Haddon & Hornell, Haywood, Holmes, Kane, Pukui